A rare chance to study the ocean before we mine it

Deep-sea miners fund deep-sea research, and other mining news nuggets

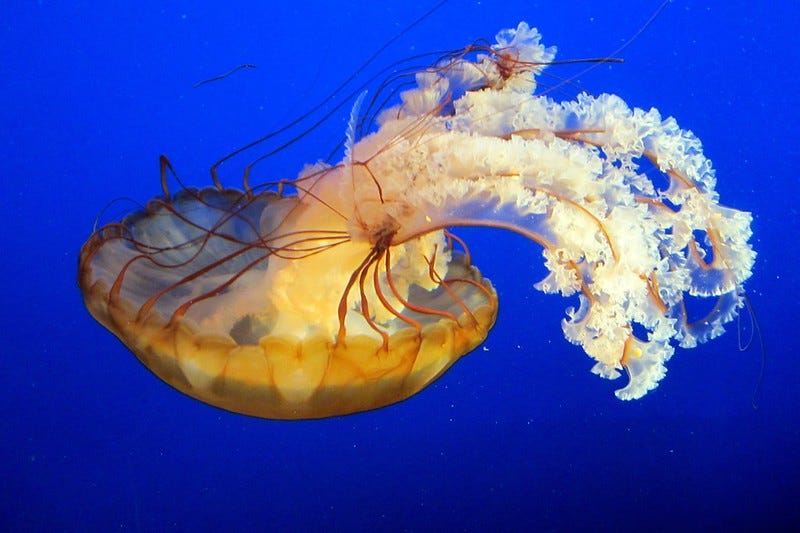

(ER Bauer via Flickr)

The deep ocean is bigger than all earth’s land, and under international law, it belongs to all of us. As a representative of the people, a UN body is crafting the rules to exploit the mineral wealth that lies on the seafloor, and it’s almost done.

But we know close to zilch about the dark depths that are already entering balance sheets. What species live there? How do they depend on each other? How are they affected by climate change? What could happen if we exhume carbon and metals trapped at the bottom of the ocean? How do we rely on the ocean?

In the biggest effort to date, a seabed mining company will fund researchers answering those questions in the area it plans to mine. One hundred researchers will use more than $60 million from Canada-based DeepGreen to gather data and insight into the least understood place on earth.

DeepGreen may become the first company to mine the deep sea. If they convince an international body that environmental impacts can be contained and minimized, they promise to channel copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese into millions of electric vehicle batteries.

It’s a climate goal, the company says, but scientists have been sounding the alarm that it may decimate the ocean in the process. Scientists know very little about what goes on in the parts of the ocean to be dredged, let alone what dredging could do to it.

The research over the next few years will help DeepGreen — and the rest of the world — understand what mining the seafloor could do to the world’s largest habitable area.

“This is a collaboration of the best minds in ocean science coming together to answer many important questions about deep-sea ecosystem function and connectivity throughout the water column,” said DeepGreen Chief Ocean Scientist, Dr. Greg Stone. “The program will enable DeepGreen to put forward a rigorous, peer-reviewed environmental impact statement to the International Seabed Authority, setting a high bar for this new industry.”

For some scientists, it’s a dream to get piles of cash to travel far and deep into the ocean to study other-worldly life. Others want to keep in mind that the company may wipe out that ecosystem.

Regardless, we may have a much greater understanding of the deep and distant ocean in a few years time.

Jeffrey Drazen is one of the more than 100 scientists who received DeepGreen funding. He’s a marine scientist at the University of Hawai’i Mānoa and an outspoken sceptic of seabed mining.

Drazen and a team of researchers will be conducting at least two cruises to the area where DeepGreen owns three of seventeen contracts to explore mining, called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. It’s west of Mexico and as wide as the continental US.

He’ll be studying “everything from microbes up to fish” with a team from Texas and Japan.

Last month, he joined with dozens of other scientists to lodge a public call to make sure regulations protect all parts of the ocean, from seafloor to midwater to surface. Other organizations have called for a moratorium on writing regulations entirely. Last week, the regulatory body published draft regulations.

“The mining code is coming out, but we’re about to have a lot more data that will affect the mining code,” he told me.

To DeepGreen’s credit, Drazen says, no other company has funded study into the midwater column. That is, everything between the seafloor and surface.

The research will become part of DeepGreen’s “peer-reviewed” environmental impact assessment (EIA) to be submitted to the UN International Seabed Authority.

“My concern is with the EIA process. The proceedings are closed. It’s not transparent,” Drazen said.

There is a risk, he said, that he will learn just enough about the new ecosystems to fall in love with them, only to have them wiped out by mining.

Dive deeper:

Deep-sea minerals could meet the demands of battery supply chains – but should they? (World Economic Forum)

A rush is on to mine the deep seabed, with effects on ocean life that aren’t well understood (The Conversation)

Seabed-Mining Foes Press U.N. to Weigh Climate Impacts (Scientific American)

Weekly InQuarry

What can the deep sea tell us?

It can tell us about the origin of life.

It can tell us how animals can build a shell out of iron.

It can tell us about exploding stars, according to a paper out Monday.

But in general, we don’t know yet what it could tell us. We don’t even understand basic facts about the deep sea. From Christopher Roterman, zoology postdoc at Oxford:

Today humans have an unprecedented ability to effect the lives of creatures living in one of the most remote environments on earth — the deep sea. At a time where the exploitation of deep sea resources is increasing, scientists are still trying to understand basic aspects of the biology and ecology of deep sea communities.

Unfortunately, the level of human activity in the deep sea has far outpaced our ability to get this basic knowledge.

Protest in Morowali, Indonesia, a nickel mining hub. (via a friend)

Eye on Industry

Cobalt mining giants created a new industry initiative to improve conditions for small-scale miners in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A similar program was launched in 2018, but disappeared after seven months. The DRC has its own plan for addressing human rights issues in mining, but so far, no foreign company has helped implement it.

Executives at mining giant Rio Tinto will have their bonuses cut after the company blamed them for ignoring signs not to demolish an indigenous site “highest archaeological significance in Australia.” No word on whether the company will continue working the site, whether the people will resign, or where the money will go.

A leading consultancy predicts LFP batteries — cobalt-free, nickel-free — will become more popular in a decade than their Co/Ni cousins. It’s also indicative of the mining companies hedging their bets among the turbulence of battery chemistries.

The US Department of Energy announced $20 million of funding to five groups trying to figure out how to find more rare earth elements stateside.

A pricing agency has begun to make a crucial distinction in the nickel supply chain. Nickel for batteries and nickel for steel are very different compounds (and produce very different waste!), but until now, they’ve been stuck with the same price. Benchmark Minerals has created a unique Nickel-for-Batteries price, which may help to distinguish the two markets.

Two of Indonesia’s biggest mining centers were shut down by protests this week. In Indonesian Papua, at the Freeport copper and gold mine at Grasberg, workers demanded safer conditions for working during the pandemic. In Morowali, dominated by Chinese company Tsingshan, workers held a strike and demanded time off.

Reads

These are not endorsements, just food for thought.

Recycling PV panels: Why can’t we hit 100%? (PV Magazine)

The Texas battery boom (PV Magazine)

The rare plants that ‘bleed’ nickel (BBC Future Planet)

One solution to California’s blackouts? The world’s biggest battery. (Grist)

Elon Musk Is Going to Have a Hard Time Finding Clean Nickel (Bloomberg)

With its mining boom past, Australia deals with the job of cleaning up (Mongabay)

Hi! I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

These topics are relevant to anyone who consumes energy. If you know someone like that, share freely! Subscribe with just your email, and weekly reports with round-ups and original reporting will come directly to your inbox. It’s free! (for now)