Biden's rare earths review & the myth of scarcity

Who benefits from the rare earths myth? A conversation with geographer Julie Michelle Klinger.

Climate technologies require enormous amounts of metal. I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

This edition has been updated.

Last week, Biden ordered his government to review his country’s reliance on the tangled web of global supply chains. Over the next 100 days, the US will look at a few key areas, including critical minerals and electric vehicle batteries.

In the wake of deadly supply shortages as a result of the pandemic, “The United States must ensure that production shortages, trade disruptions, natural disasters and potential actions by foreign competitors and adversaries never leave the United States vulnerable again.”

In the Great Tech Push to stop emitting greenhouse gases, the US is focused on autonomy. Biden’s predecessor also fought for independence in manufacturing, although Trump was explicitly on a quest to counter China’s dominance. With climate technologies, this executive order will evaluate China’s “tight grip” on metals, particularly rare earth elements.

But what happens when rare earths become almost mythical? To explore the answer to that question, I caught up with geographer Julie Michelle Klinger on Tuesday.

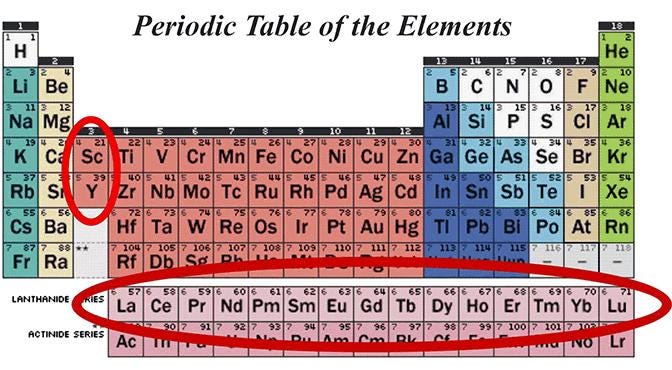

“Rare earths are not rare.” That’s the first line of Klinger’s book on these 17 elements. In Rare Earth Frontiers, she tracks the political forces fueled by myths about frontiers, empty spaces, global competition, and crucially, the term ‘rare earths’ itself.

They’re used in a wide range of technologies, from missiles and medical equipment to electric motors and wind turbines. In 2010, they began making headlines. China stopped a routine shipment of rare earths to Japan, which used them for electronics manufacturing. Before scientists could clarify that the elements are some of the most abundant on earth, media latched onto the term ‘rare.’ Investors looking to cash in on building more projects raised the alarm that China produced almost all of the world’s supply. They employed other rhetorical devices like “gold rush,” too.

“It’s not gold. It’s not like you possess value as soon as you hold it. It needs to become something else, and that’s very involved process,” Klinger says. (The same ‘gold rush’ phrase shows up often in climate metal reporting.)

It’s that process that has left destruction in the wake of industry. It’s notoriously hard. It’s especially hard if you want to do it without leaching harmful waste into waterways or exposing workers to excessive radiation. China’s weight in the industry is largely a result of the US escaping these issues a few decades ago. (see below)

The term ‘rare earths’ is largely a relic of 18th-century miners who hadn’t seen the rocks before. Scientists found that the elements often appeared together, grouped them, and created specializations for those 17 elements. To some extent, rare earths have unique conductive and magnetic properties, but those aren’t limited to just that group. Perhaps a reason the term endures now, Klinger writes, is because it justifies “the relentless pursuit and capture” of these rocks.

“It can obscure more than it clarifies,” she says.

‘Rare earths’ is a poignant rhetorical device. It embodies a myth of scarcity, and it conceals the unique, constituent elements and their properties. What results is a black box buttressed by apparent necessity, and it’s difficult to see inside.

“Whether it’s rare earths or critical materials, if a company can turn around and say to investors, ‘Hey, this is critical. Even the US government says so.’ That is great for the company, because it’s likely to boost and bolster investor confidence and likely to increase the value of their operation. On the other side of it, when something is called rare or critical, it becomes much more difficult to oppose it without really really getting into the nitty gritty or developing a sophisticated knowledge set around what the empirical realities are in terms of available supply, available resources, [and] are they rare or not?”

After Biden’s announcement to review rare earths supply, some companies have already begun cheering it, with one saying “Rare earths and critical minerals, including lithium, are essential to modern technology and require a robust, resilient strategy for U.S. advanced manufacturing and national security.”

“While I think it’s imperfect to refer to rare earths or critical materials as a single group, I think it’s a valuable tool for policymakers and useful for business,” Klinger says. “This doesn’t mean that it matches geological reality. This is just a reflection of how we’ve organized our supply chains — or rather how we’ve failed to organize them.”

So far, Klinger says, discussion about critical metals has followed the needs of the US military, the largest in the world. Is cerium ‘critical’ because it’s needed for LED lighting or polishing in military uses? Are dysprosium and neodymium critical as magnets for wind turbines or for military uses? If scandium is used mostly for aircraft and spacecraft, does it need support for the energy transition?

“Although the military supply chain really dominates the conversation — in a way that I think is actually detrimental — it’s not the only game in town,” she says. “With respect to the latest executive order, I’m encouraged that this administration is taking a broader view and it’s looking at manufacturing capabilities in the rare earths supply chain, instead of the much narrower view of the previous administration which was about mineral sourcing specifically for the military.”

The roots of this latest executive order come from the US’s unease with relying on China. The news came with a healthy dose of news that said the US was “combatting” China, its “adversary” and “rival,” which has a “tight grip” on rare earths. A Reuters story this week framed a contentious mine in Greenland as a battle between China and the West. Lingering over most analysts minds are rumors that China has left the door open for using rare earths as a geopolitical tool.

But the Chinese government is also wary of the pollution the industry has been creating in its country. This year, it proposed tightening regulations to stifle illegal mining and prevent environmental harms. Recently, it began importing more rare earths than it exported.

China’s current dominance may have been unlikely without help from US mining contractors, and in particular Edward Nixon, the brother of Richard Nixon. In the early 1980s, Edward reportedly proposed that mining executives process their ore in China, and he facilitated trainings for workers there. Miners benefitted from cheaper production costs, and the US outsourced the environmental hazards that produced radioactive and carcinogenic material.

Nevertheless, leveraging anti-China sentiments has become commonplace. “I think that whole discourse is really deficient,” Klinger says.

“I think it completely washes over the fact that China and the rest of the world have shared interests in the global supply chain. I mean, China does not want to be the primary producer or primary exporter of rare earths, and the rest of the world does not want China to dominate it. That’s a one-to-one complementarity there, and that’s entirely lost in how it’s framed, that China is out to get the rest of the world.

The scramble to mine rare earths in places like Greenland and Afghanistan fit into this New Cold War, neocolonial rhetoric. It’s reminiscent of the European colonial scramble for Africa. It’s also reminiscent of the Cold War between the US and former Soviet Union, where you have these powers competing to lock up resources — not because they necessarily need them, but because they feel that it would be advantageous to have control over them.”

So if the myth of scarcity and of China-versus-West both rest on shaky ground, what’s next? In 2017, China and a few other countries began pushing to standardize the industry and create internationally recognized environmental standards. They’ve only gotten as far as agreeing on vocabulary. In December, the Rare Earth Industry Association began the process to regulate itself.

There are potentially extensive deposits spread outside China already, and they’re either in your home or the landfill. Currently, 99% of all the rare earths go straight into the trash after use. Just 1% are recycled. However, the technology to recycle exists, even if just at small scale.

“I think we could solve a lot of our supply concerns if we just figured out how to scale recycling,” Klinger says. “I’m just going to do a sort of back-of-the-envelope thing and say that with a five-to-ten-year ramp-up [of recycling], I think we could easily take care of more than half of our current demand.”

But it’s hard to find where these ‘deposits’ of metals would be and how to get them. Can we return to old airplane graveyards and e-waste landfills and extract what’s left? How do we encourage people to go through the electronics in their basements and hand them over to recyclers?

If recycling projects take at most several years to construct, mining projects can take decades. Because rare earths mining require complex and wasteful processing, building out domestic supply in the US, Canada, or EU could take much longer. Long squeezed for funds, two rare earths miners are exploring the public trading route, but these are baby steps compared to the processing and manufacturing facilities needed to match other producers. For readers in Texas (the closest thing I have to a home state), expect a miner and processor to appear in the north.

Thanks for reading! These topics are relevant to anyone who consumes energy. If you know someone like that, pass this along!

So has this article been updated or expounded upon since the actual EO came out? I heard, and correct me if I'm wrong, but is it true Biden is shutting down American mines and buying the REM from China exclusively?

Great piece! Thanks for the good reporting!