How China warped the market for a vital clean energy ingredient

Penalized at home, aluminum makers figured out how to outsource mines

To keep our planet from warming more than 2ºC, we will need clean energy technologies. Those gadgets will demand a lot of metal, and none more so than aluminum.

But producing aluminum has the highest potential of warming the earth further. And in the last decade, mining for it has become a lot less friendly to its neighbors.

In this post, I want spotlight the earth-shaking importance of a dull, red mineral called bauxite — and the impacts of China’s recent industrial globalization.

Let’s dive in.

This will demand a lot of aluminum. (Activ Solar via Flickr)

For this piece, I spoke with:

Zhang Jingjing, environmental lawyer, Lecturer in Law at University of Maryland Law School, and founder and director of China Accountability Watch

Alan Clark, founder and director of CM Group, a leading minerals consultancy.

I don’t think I’ve learned how to type the above spelling of Aluminum, so I will maintain my Americanisms for now. (Science Activism via Flickr)

Aluminum Affairs: Sun, Smoke & Society

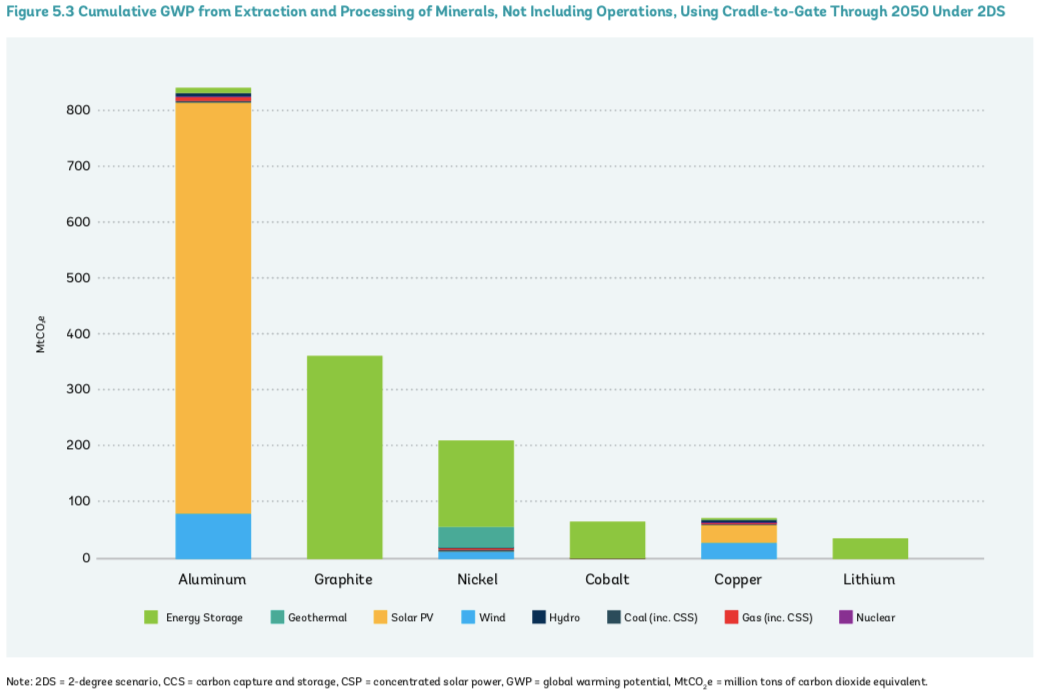

To keep the planet from warming past the point of no return, the World Bank says, more metric tons of aluminum will need to be mined than any other metal.

Sun: If the bank’s projections from May are correct, almost all of it will be funneled into solar PV. Solar panels, in fact, are almost 90% aluminum. It’s corrosion-resistant, lightweight, and strong.

In the calculations below, the World Bank only included the energy technologies that use these metals. Demand for aluminum and other metals would likely increase further if all associated products, like aluminum-based electric car parts, were included.

Aluminum is the red bar. On the right, the graph shows aluminum will experience the most absolute demand growth. Relative to its total production now, it’s quite small, as shown on the left. (World Bank)

There are a few issues, though. Aluminum production is among the most energy-intensive of all mineral industries. In total, the mining industry causes at least 10% of the world’s carbon emissions, according to the World Bank.

Aluminum usually starts in the earth in a mineral called bauxite. After one round of processing, it becomes alumina. After another round, it becomes aluminum.

In all these steps, refining requires hefty amounts of electricity to extract the right products from a soup of metals and compounds. In addition to the energy required, carbon is released when aluminum is separated from its natural form.

Smoke: As a result, the aluminum to feed solar energy — perhaps the most promising renewable energy source — may also create the most emissions and pollutants.

But ten years ago, even close observers of the aluminum industry could not envision how bauxite mining is structured today, says Alan Clark. Bauxite mines have recently been dispersed around the world. Market analysts used to believe that was impossible. It’s no coincidence that those mines are often found in areas with little environmental oversight.

Society: A market overhaul has fueled a “boom in bauxite” that has threatened chimpanzees in Guinea, water supply in Ghana, respiratory health in Malaysia, and river health in Indonesia. Last month, dozens of community organizations in Ghana advanced to the High Court in a lawsuit against their government to stop a bauxite mine.

What was the bauxite shake-up?

China has been the top producer of aluminum for a long time, but most of their bauxite no longer comes from within their borders.

In the past decade, a motley crew of political, market, regulatory and engineering changes has opened the world to China’s aluminum producers.

“The very notion of importing bauxite into China from a range of different countries and processing through merchant refineries — this is something most of the industry never thought would happen because, historically, the industry was based on the mine-mouth-to-refinery model,” Clark told me.

Companies typically built refineries right next to their mines: a ‘mine-mouth model’. The composition of bauxite differs widely around the world, so it was difficult to “chop and change” ores to suit different refineries all at once. Smelters had to be designed for a specific kind of ore.

But China’s capacity to process bauxite was massive. It became easier to find a refinery that could handle foreign ore as the number of refineries ballooned. With dozens of small refineries, only China could import ore and avoid the loss of efficiency.

Then, Indonesia flexed its muscles. In 2014, it recognized foreign companies were sending its valuable dirt abroad and gambled to reign in that value. It banned the export of bauxite.

Bauxite. (USGS)

The event spurred China to begin looking all over the world for bauxite. Malaysia was an obvious target for its location and infrastructure for exporting iron ore.

But the industry moved too fast for regulations to keep up. Malaysian bauxite production ballooned to 100 times its previous size. Malaysian communities quickly began complaining of dust and rivers that began to run red. Malaysia banned all bauxite mining just two years later.

While this was happening, the Chinese government was becoming increasingly aware that its domestic mining and processing was polluting its own citizens’ lungs. The government responded with stricter anti-pollution rules in 2015 that allowed public interest lawsuits, forced local governments to enforce environmental regulations, and removed the ceiling on pollution fines.

From a report prepared by CM Group for the Australian Stewardship Initiative.

Bauxite refiners, wary of domestic sanctions, “scoured the world,” Clark said, exploring deposits in Fiji, Brazil, Jamaica, and India. But only in West Africa did Chinese companies see potential.

“Guinea became the obvious target, and development started happening fast. Very fast,” Clark said. A consortium of Chinese and Singaporean companies rapidly lifted Guinea to a top exporter of bauxite to China with the help of another joint venture of US, Anglo-Australian and Guinean companies. Last year, Guinea mined more bauxite than China for the first time.

What impact did that have?

When companies were globe-trotting in search of bauxite, they eyed Australia’s massive reserves. Chinese companies steered clear, though, because the country’s regulations prevented them from investing in control over projects, says Clark.

Globe-trotting (my word, not Clark’s) meant companies could choose locations that minimized their costs but maximized their profits, says Jingjing Zhang, who has been involved in community lawsuits in Guinea and Ghana. Regulations in certain countries could increases costs, while companies can take advantage of nature’s carefully crafted ores in other countries.

But, as Zhang points out,

In a short period of time, companies can make a quick fortune by taking advantage of the weak institution. But in the long run, the weak regulations will bring risks to companies and affect companies' operations, like the weak environmental regulation may cause an environmental disaster, which will trigger societal conflicts.

Bauxite mines and refineries often produce well-documented “red mud” that ends up clogging and contaminating waterways. In West Africa, Zhang has documented the problems that mining has caused local communities, including

Water pollution and the shortage of groundwater caused by the mining operation,

Impact on water resources both on quantity and quality,

The dust from mining roads, especially in dry seasons, affects people's health and crops, trees,

Safety issues for children who have to cross mining roads to their schools,

Losing lands, losing their livelihood.

She alleges that some companies have fallen through on their promises to build and repair facilities like roads and wells for locals.

Bauxite mine in Australia. (Wikimedia)

In Indonesia, as Clark notes, bauxite miners left gaping holes in the landscape after they failed to remediate mines after closure. A provincial governor has complained that 260 mines abandoned the open-pit mines that continue to erode into waterways. Malaysia lifted the ban on bauxite mining, even as locals experience continued health impacts.

One organization found that in Guinea more than 100 water sources and 80 square kilometers of crop land were lost to mining activities. In 2018, Human Rights Watch said mining operations in Guinea had threatened thousands of livelihoods and left homes coated in dust. In Ghana, China-funded projects are prepared to mine two areas designated Globally Significant Biodiversity Areas.

To be clear, Clark doesn’t believe it’s fair to reduce the movement of Chinese-funded and connected bauxite mines abroad to the pursuit of regulatory environments where businesses can “get away with more.” Chinese domestic reserves of ore (although based on business-reported numbers) have been approaching depletion for several years. Cost, though, remained a factor, he said: “If [Chinese refiners] can build and operate a refinery cheaply, that would be a primary driver.”

So what is to be done about all this?

The World Bank’s roadmap for aluminum in solar panels offers a point of leverage. Clean technologies should have clean supply chains, and the tiny fraction of aluminum that will be made into solar panels can become a model for the rest of the industry.

This has been Part 1. In the second half, I’ll explore what is being done and what can be done. Subscribe so you don’t miss an edition.

Further Reading:

Ghana’s government faces pushback in bid to mine biodiversity haven for bauxite

Bauxite mining and Chinese dam push Guinea’s chimpanzees to the brink

How does 2020 bode for China’s overseas investment? A Chinese lawyer’s take

Hi! I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

These topics are relevant to anyone who consumes energy. If you know someone like that, share freely!

If a friend forwarded this to you or you just arrived here, you can subscribe with just your email, and weekly reports with round-ups and original reporting will come directly to your inbox. It’s free! (for now)