Nickel's future in a school, an island, and an ocean

Everyone is talking about nickel, so I have to chime in

I need to write about nickel, because everyone has been talking about nickel, and because I spent almost three years living in and reporting on the world’s home of Big Nickel.

You can also thank Elon Musk’s characteristically coarse comments on an earnings call, then his tweets hammering the point home: He wants more nickel, more cheaply. For someone who tripled his billions during a pandemic, his voice is his capital, and his capital boosts the resource extraction that concentrates wealth in the global North while elsewhere decimating ecosystems and collecting debt.

Jumping on the buzz were Bloomberg, Financial Times, Teslarati, InsideEVs, CleanTechnica, and other outlets whose reporting has typically followed the user end of the supply chain.

Nickel — whose industry has been dubbed second least sustainable after cobalt — is staying in batteries, and the goal is to produce as many batteries as possible.

There have always been alternatives that can be kinder to the world and its people. But those who believe in them don’t have the platform of a multinational company. They have their stories.

The School

I’ll tell you first about a school.

Batu Putih public high school is in the center of Sulawesi Island, in Indonesia. It’s a day’s trip from the nearest airport and shopping mall. Locals have pushed to protect the surrounding forested mountains in a national park.

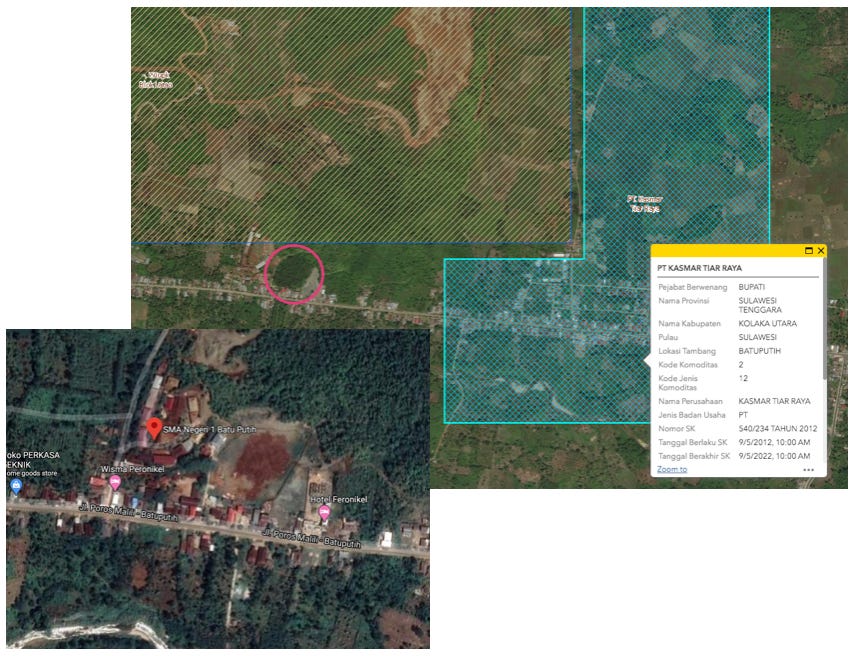

There’s a mining area a kilometer away from the school, but in February, mining equipment appeared on school grounds. Over the next two months, company workers dug up the school yard.

Next to the school is Hotel Feronikel, named for the nickel compound used in steel. The owner told me mining equipment was still at work on the grounds. A local village head told local media that teachers had agreed with the company to plow their schoolyard.

“They said they were just fixing the schoolyard at the request of the school, but the fact is they had piled up ore for sale,” Yarip, a local activist, told me.

There is little available information about the company, Kasmar Tiar Raya, but it has been at the center of conflicts for years. In 2017, a company official said it sold nickel ore to Anglo-Swiss commodities giant Glencore.

In April, locals reported to the police that Kasmar was mining illegally. In July, the provincial licensing authority concluded that Kasmar and two other companies were mining illegally. Locals have lambasted their officials for failing to halt operations.

“They barely uncover anything, then just leave the companies alone,” Yarip said.

On Tuesday, the companies were surprised with a sudden inspection from the province’s mining authority.

The Island

More nickel projects are coming to Indonesia. One of those mines is on Wawonii Island.

Life on a small island is supported by resources available in immediate surroundings. Settlements grow near water springs, and what protein the land cannot provide, the sea makes available in excess.

Such is the case with Wawonii, where tens of thousands of residents were a bit surprised one day to find police escorting an excavator through the forest, tearing down their cashew and nutmeg trees. When locals asked why, the company responded: we have all the necessary permits.

When I arrived there for a Mongabay story, people had already constructed sheltered battle stations to occupy and demarcate their land (above). The company had made efforts to convince some residents that it would bring prosperity. Families were set against each other, and some were employed as de facto press agents. Mando, a young community leader, said it was a “social conflict.”

Mando and much of the island were furious with the company, even before they understood why the company had come to Wawonii.

Such a mining company, industry leaders say, is critical to providing the lithium-ion batteries for our clean energy future. After leveling part of the island, the company owned by the Harita Group plans to dig up ore, send to another island for processing, then ship to China to be funneled into batteries for clean energy.

While they make battery material, heaps of coal will power smelters, and metal-rich soil may flow into waterways and poison drinking water, killing corals and repelling fish. For roughly every ton of nickel and cobalt produced, the company plans to dump more than 100 tons of waste into the ocean.

When I told Mando this, his reaction showed me this was nothing new. In Indonesia, the top producer of nickel ore, it isn’t. Clean energy or not, the final product had never mattered on islands dug up for ore.

The company reported 27 people to the police, and a few of them were charged with impeding business activities. This year, the national government made nickel mining a national policy, armed with the power to acquire land as it sees fit.

Chinese battery firm GEM announced yesterday it would buy nickel and cobalt from Harita’s project that plans to source ore from Wawonii.

The Ocean

Most of the world’s battery nickel may soon come from a few new plants in Indonesia. There is one almost identical project, and it describes what we may expect to see soon in the ocean.

For two decades, locals in Papua New Guinea have protested a nickel mine in their mountains and a smelter on their shores. The smelter dumps several million tons of waste into the ocean each year.

In 2011, they argued in court that the plant would endanger their lives and undersea lives in the world’s most biodiverse coral hotspot. They lost, and the Chinese company, Ramu NiCo, began channeling materials into the world’s batteries.

Last year, a small spill prompted the local government to begin studying what the plant had done to the ocean over the previous 7 years. Three more spills happened, a man died, and local groups sued again.

Ben Lomai took the case. He’s the same lawyer who represented hundreds of refugees in a wrongful imprisonment case against the Australian government. The case against Ramu, he said, may be the biggest environmental case in the country’s history. His clients allege that seven years of dumping waste into the ocean has contaminated water sources with toxic metals, killed marine life, and put people at risk of birth defects.

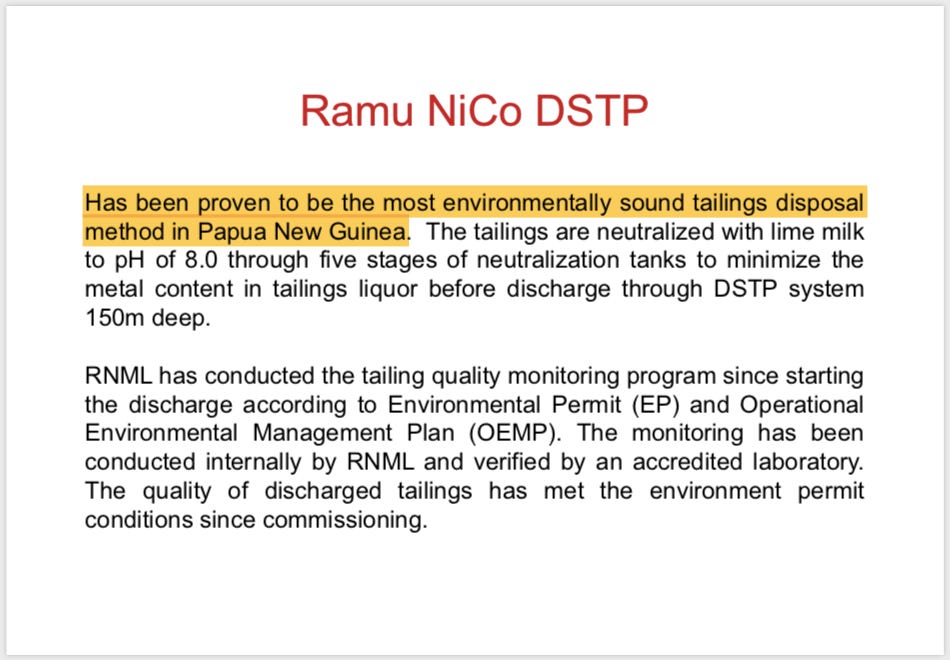

A month before Lomai filed the case, mining companies presented their case for ocean dumping to the Indonesia government. The companies are aiming to build at least four smelters almost identical to the one at Ramu. Below, a slide from the presentation (DSTP = ocean dumping).

Locals in Indonesia have begun mobilizing. They’ve staged protests and written reports on the impacts. The Mining Advocacy Network, an Indonesian NGO, predicts 10,000 fishing families will be affected by the sudden surge of waste into the ocean.

Abdul Haris Lapabira runs a local environmental NGO and coordinates with fishermen near mines. I asked him what he would say to a battery company if he were given the chance. He said:

The industry you’re creating will destroy any hope we have for living sustainably with the ocean. It will destroy the future of our generation.

Hi! I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

These topics are relevant to anyone who consumes energy. If you know someone like that, share freely! Subscribe with just your email, and weekly reports with round-ups and original reporting will come directly to your inbox. It’s free! (for now)