Report: Battery supply needs transparency

Author Q&A on opportunity and roles of consumers and activists

Late last year, two legal research institutions brought together business leaders, researchers, and activists for a conversation.

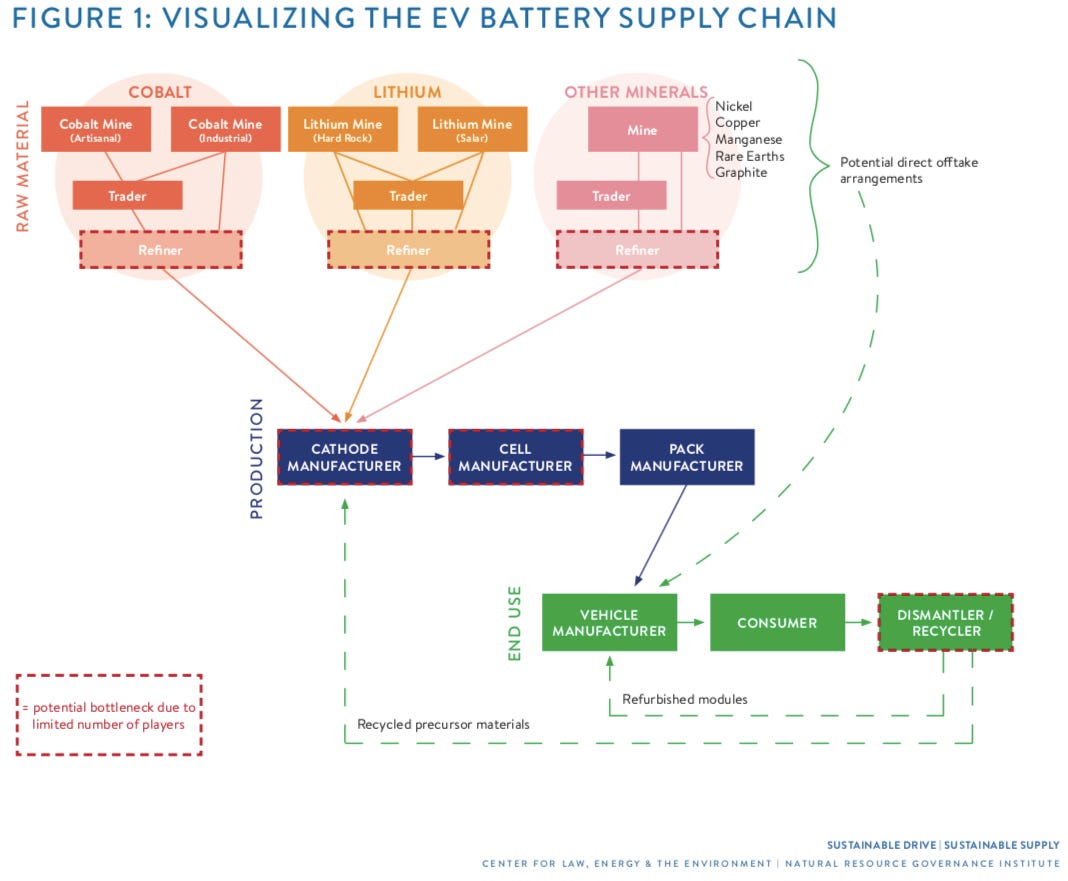

Their goal: to find solutions to issues in the electric vehicle supply chain. Batteries, specifically, require hefty amounts of metals, and demand for a billion or more EVs means miners have a golden ticket to harvest more of the Earth’s crust.

The Natural Resources Governance Institute (NRGI) and UC Berkley's Center for Law, Energy & the Environment (CLEE) understand that more mines will be dug, but the EV industry has an opportunity to distinguish itself from its counterparts in the metal industry.

Today, they released their recommendations for what they see as the top three challenges in the industry. At the foundation of a sustainable supply chain — meaning one that equitably distributed wealth and resources and minimizes damage to the Earth and its people — is transparency.

However, as co-author Patrick Heller tells me, economic development led by mining has rarely worked. Below is our lightly edited interview. He’s a legal advisor at NRGI and has been promoting good governance in mineral and oil-producing countries for twenty 20 years.

You might still have time to jump on the webinar! I’ll be there, and my main question will be this:

The report’s recommendations rely on strong transparency, but the path to open information is still murky. In one recommendation, companies are meant — on their own initiative — to inform consumers about their practices. There are, however, no incentives in place for that to happen. How will transparency actually be achieved?

The challenges and solutions from the report:

A lack of coordinated action, accountability, and access to information across the supply chain is an important root cause of supply chain mis-governance.

Addressing this requires stronger mechanisms to improve data transparency and promote neutral and reliable information-sharing, to level the playing field between actors across the supply chain and between governments and companies.

Coordination and data-sharing across multiple supply chain standards is weak, which can hinder adherence. The report lists 9 market initiatives and 9 legal mechanisms.

Stronger systems to help supply chain actors prioritize and coordinate across these standards, along with a stronger set of incentives for rigorous application, would promote more consistent application.

Regulatory and logistical barriers impede progress on battery life extension, reuse and recycling, all of which can reduce demand for mining.

Priority responses include designing batteries proactively for disassembly for recycling and reuse, building regional infrastructure for battery recycling and transportation, and creating regulatory certainty for recycling

So, while metal-rich countries have the chance to capture some revenue from the demand for mining, the ultimate goal is to reduce demand for mining itself. And in the meantime, transparency will enable accountability for the metals that end up in EV batteries.

I spoke this week with co-author Patrick Heller to learn more. Below is a trimmed Q&A on what makes the EV industry unique and how the industry should move forward.

TL;DR — EV supply is rapidly changing, and it leads with the brand of ‘clean energy.’ It’s on companies to decide that they should invest more in transparency, and it’s on consumers to push them that direction.

What is specifically different about the EV industry that presents benefits or drawbacks for managing and proliferating sustainability throughout the supply chain?

Why do there need to be reports specifically on the EV industry?

Well one, it’s obviously incredibly critical for the future of the planet that the world shifts away from internal combustion engines increasingly toward the use of electric vehicles. There’s no hope in tackling our climate crisis unless we make progress on that front.

The second is that there’s an opportunity here. If we really do see the explosion in demand that some people are projecting, there is a significant opportunity for mineral-producing countries to take advantage of what’s happening in the EV market and in clean technology markets more broadly, and to use that to help amplify their mineral sectors to the benefit of broader economic development.

With that being said, mineral-lead development has failed in many countries. The industry is complex. It involves the need to bring in powerful global players. It can attract unscrupulous actors. There are a lot of reasons and a lot of root causes that have impeded the development goals of a lot of countries that have wanted to use mining as a centerpiece, and it created other problems with very serious impacts.

As we are approaching this work, we are thinking quite a lot about the question that you pose. What is it about the nature of this industry in particular that might create very meaningful opportunities? What is it about this industry that makes those opportunities challenging to realize, and therefore it creates an imperative for all of us to take this issues very seriously?

There are a couple of things that I think are unique in this space.

One is that the EV sector and its supply chain are evolving rapidly. They are complex. They involve players, some of which have not been very deeply exposed to international transparency and reporting requirements. And therefore, there’s a lot of confusion out there about how to tackle the challenges most effectively and where the opportunities really lie.

In a lot of the countries we’re working on, there are huge ambitions [such as] ‘Our country is going to become a leading producer of mineral X, and we’re going to be able to exercise really significant power in the global marketplace, and we are going to start producing batteries within our country.’ The complexity and the rapidly changing nature of the supply chain makes it very difficult for the people who are projecting those ambitions to analyze and scrutinize in a systematic way where those opportunities do lie, and what’s an illusion and what looks real.

The second particular area of difference that we’ve been looking at is the nature of what electric vehicles are, and what they are intended to be, which is a clean energy solution to the biggest problem facing the climate right now. And as a result of that, I think there’s an important additional scrutiny that’s on this industry, and I think that’s a scrutiny that can be mobilized and used in order to draw attention to and shed light on some of the challenges and, again, some of the opportunities that exist in these producer countries.

People who buy EVs are in many cases doing this because they care about the future of the planet, or at least that’s an important part of that decision making process, and therefore there is an opportunity to draw and capitalize on that to bring some attention to address some of the base problems here.

From the report

The report indicates that responsibility for issues in the host country has been placed overwhelmingly on mineral companies in the host country. When downstream players play a role, they typically align with private actors’ priorities in that host country.

What opportunity, if any, is there for downstream players – such as Tesla and others – to address issues in the host country in a positive way?

I won’t pretend to have a completely conclusive answer to that question, but here’s some of what we’ve been looking at.

The downstream players are participating in this sort of proliferation of international initiatives that are looking at what’s happening along the supply chain. Our consultations and the interviews that we’ve done for this project have indicated that there is a reticence on the part of the downstream players to get too deeply involved in what’s happening in the producer countries. And that’s understandable. That’s not their business to be deeply involved in economic decision-making and negotiation in the mineral-producing countries.

Our consultations have indicated there’s an opportunity for these downstream players to be playing a little bit more proactive role in encouraging stronger standards for their suppliers down the chain… We think these downstream companies have a significant enough market power collectively that encouraging stronger standards around governance within the producing countries would be an important step that they could take that could push things forward in that meaningful way.

I think these companies are taking these questions seriously, but there’s a little bit of a reticence that we keep hearing about to really put pressure on their suppliers to change the way that they do business.

What incentives are in place in order for those kinds of things to happen? To allow downstream players to play an active, positive role in upstream activities?

There’s a couple of things that I think are underdeveloped, and I hope to see more developed. One is the international supply chain initiatives; really building out in a more comprehensive way, what they mean by governance and what they mean in terms of the fundamental relationships between companies and government and nongovernmental players in producing countries. I think there’s a collective responsibility for the downstream players and their upstream partners to engage in something that is a more fundamental discussion about what their roles are in these various countries through the various international mechanisms.

And secondly, one of the things that came out fairly strongly in our consultations is the need to more constructively harness the ways in which consumers are starting to pay attention to these questions in a manner that can result in a more information-rich approach to the commitments that companies both upstream and downstream are making. So right now, consumers express concerns and companies are left feeling to some extent like, well, no company feels that control of these decisions are in their hands. We think that if players across the supply chain took a more proactive role in defining and developing a kind of consumer-facing approach to defining and communicating what their standards are, that could take advantage of that consumer pressure more effectively to impact what’s happening along the supply chain.

The report offers something similar as a potential “quickest path” to sustainability.

In my view, to take advantage of these opportunities and to reduce the risks requires coordinated, effective action among the industry players up and down the supply chain, including a consumer-facing set of standards and process of communicating how companies are doing up against those standards. It also involves really significant investment by international financial institutions and donor governments in supporting the capacity of good governance in the producing countries.

And it requires continued activism by activists, journalists, researchers, in the producing countries themselves to make sure there is accountability pressure that’s happening on decision makers at the country level. So in my view, this kind of confluence of action by businesses, western governments, producing country governments and activists is going to be necessary if this is going to evolve into a more sustainable, long-term supply chain.

Ten points to whoever guesses where this is and shares this post.

I want to make sure to touch on the theme of transparency. It came up a lot [in the report], especially with regard to the history of the minerals sector being not the most communicative and not the most transparent. What incentives are in place, or what incentives could be put in place in order to make the EV industry different?

Yeah, great question. So, I want to start by saying that there are some important transparency initiatives that are playing a role here in a meaningful way. [Examples:]

The OECD guidelines on supply chains have important elements in them related to disclosures that companies need to make, both about their supply chain and about the impact they’re having in country.

The London Metals Exchange is trying to set up new guidelines that would require any company that trades metal on the exchange to publish significant amounts of information about what it’s doing in country.

The Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative gathers many of the most important mineral-producing countries that are impacted by this with a strong set of requirements that they have to disclose.

In my mind, it’s a question of strengthening international standards, rather than creating new ones. The standards that relate to non-human rights issues could stand to be better integrated, and built out more and more as these initiatives evolve.

And again I want to emphasize here, too, the role of action that’s going on within countries. It’s really critical. I’m sure you’re well aware of it, having spent so much time working on this stuff in Indonesia. There’s a big risk with all of these initiatives that they stay at this 30,000-foot level. It’s really critical that activists and government reformers within mineral-producing countries continue to emphasize these issues and that those outside those countries continue to do what they can to support and empower those activists.

At the end of the day, it’s the reform that’s taking place and it’s the systems of accountability mechanisms that are being put in place within the producing countries themselves that will be the most important determinants of how effective supply chain sustainability efforts are. The structure of the international marketplace has a huge influence on that, and so we want to make sure that we’re targeting that information to the international community, but it will never be a substitute for the importance of accountability within the producing country.

So you would advocate for continued weight on the producing countries.

Definitely, yeah, that reform and capacity development within the producing countries is really at the core of all this.

What can the role of consumers be in all this?

Great question. One, I think it’s important for consumers to keep things in context and keep things in perspective. The efforts by the fossil fuel industry to say, ‘electric vehicles are just as dangerous to the planet as oil’ – consumers should be leery of the motivations of those kinds of campaigns.

But two is for consumers to be, while recognizing the promise and the importance of electric vehicles, to remain cognizant of the impact the production of these vehicles is having on people’s lives. And to be encouraging companies at various points on the supply chain to be investing in sustainable development in the producer countries, and to be investing in developing serious processes for avoiding the most serious risks, you know, environmental damage, corruption, human rights.

That’s a pretty generic response, but I think consumers are nuanced and trued and are thinking. I think there is plenty of room for consumers to say, ‘EVs are the path to the future, and it is important for the industry to develop as sustainably as possible, not just because we care about the planet, but because in order for the industry to survive and thrive, these challenges need to be tackled in a serious way.’

It sounds like transparency, then, would have to be the foundation for a lot of these things. Would you agree with that?

Yeah I think so. I think it’s right at the core of this.

Which would be a momentous thing if it were to happen.

Yeah, yeah, I mean the hurdles are big certainly, but I’m not as pessimistic as others.

Hi! I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

These topics are relevant to anyone who consumes energy. If you know someone like that, share freely!

If a friend forwarded this to you or you just arrived here, you can subscribe with just your email, and weekly reports with round-ups and original reporting will come directly to your inbox. It’s free! (for now)