Mines produce more waste than metal

Two experts spoke out about inordinate industry power over a landmark process to prevent deadly waste disasters

Climate technologies require enormous amounts of metal. I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy.

The energy transition has found itself in the hands of mining companies, right as those same companies confront a major crisis of credibility.

Mines produce metals, but they also produce waste, including tailings. In most cases, in fact, tailings overwhelmingly exceed the metals that later goes for sale. In terms of quantity, waste is the main product of a mine.

Yet, in the decades that large-scale mines have produced most of the world’s metal, tailings has been an afterthought. Mining companies typically employ more people who extract metal than they employ to manage the rocks that aren’t their target. One of the most common ways to deal with tailings is to store it nearby.

These structures, often called tailings dams, are among the largest human-engineered structures on the planet. They don’t look like your typical hydropower dam (and definitely not like a beaver dam). They are stuck in valleys or artificial pits, held in place by walls of hardened earth. That wall holds back the waste, which is in a state between liquid and solid.

If the demand for metals in climate technologies open more mines, we will also see an exponential increase in tailings.

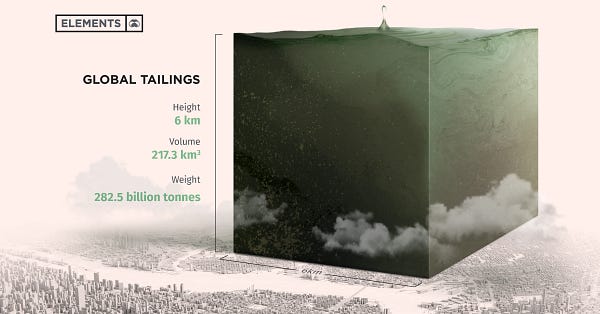

The Visual Capitalist recently mapped out what all the world’s (estimated) tailings would look like together:

In 2019, one of these tailings dams collapsed in Brumadinho, Brazil. A wave of waste smothered buildings and killed at least 270 people. Four years previous, another tailings dam broke in what was called Brazil’s worst environmental disaster. Since 1995, an average of 2.6 dams every year failed around the world, according to researchers who also say they likely missed some.

The Brumadinho collapse catalyzed investors. Several funds told industry that they would take their money elsewhere if something wasn’t done to prevent such destruction from happening again.

So, the International Council on Mining and Metals, an industry association, initiated the Global Tailings Review. The review established industry norms that aspires to achieve “zero harm to people and the environment with zero tolerance for human fatality.” The ICMM brought in the UN Environment Program and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) to negotiate a global standard. The group also took advice from a seven-person expert panel. In August last year, the review unveiled in a 40-page document the first ever global tailings standard.

Then, earlier this year, two members of the expert panel, published a book that described their experience in the creation of the Standard.

“The bottom line is that we wrote the book because power was imbalanced,” says professor Deanna Kemp, the director of the Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining in the Sustainable Minerals Institute at the University of Queensland. Co-authored with Andrew Hopkins, an emeritus sociology professor at Australian National University, the book is called Credibility Crisis: Brumadinho and the Politics of Mining Industry Reform.

Kemp and Hopkins say industry did not follow the rules they themselves had agreed to. Companies, represented by the ICMM, were meant to have the same level of power as the UNEP and PRI.

“These three, apparently equal parties were not equal. The ICMM had far more power in relation to the final outcome,” Hopkins told me. “They believed that their interests were more important than the interests of anybody else. They said that to us quite explicitly.”

Additionally, Kemp’s and Hopkins’ expert panel could not act independently. Just days before the panel were to publish its draft proposal, CEOs from the ICMM deleted significant sections and adjusted wording.

“The public did not get a chance to respond to our initial recommendations,” Hopkins said. “We were pressured in various ways by the ICMM to recognize their interests and make sure their interests were properly recognized in the standard.”

Kemp and Hopkins pushed for various measures to be accepted into the Standard. Some made it, many did not. Here are a few.

Should companies obtain free, prior, and informed consent from communities for their operations? Hopkins says there were “huge fights” around this, and the destruction at Juukan Gorge last year forced companies to confront consent. Companies, however, did not want to be required to obtain consent, but rather “work to obtain” it. Obtaining consent is not required in the final draft, and “working to obtain” it is only required with projects that would “significantly impact” Indigenous groups.

Should communities have a right to participate in discussions about construction and management of tailings dams? Kemp and Hopkins write that the final wording is unclear. Communities were not directly represented in the process.

Should executives be accountable for tailings dam failures? The final Standard does not require an accountable senior-level employee. If accountable employees are lower down the chain of command, it’s easier for companies to have a scapegoat who can be easily fired.

Should tailings management influence executive bonuses? Incentives to boost production and profits can lead to safety hazards, even though they may result in colossal bonuses for CEOs. Partially as a result of Hopkins’ pressure, the Standard requires tailings safety play a role in those bonuses.

Should the ICMM ban certain types of dams that experts say are most dangerous? Several countries have banned upstream tailings dams, the kind that burst in Brumadinho. However, before the process began, the ICMM said members were not allowed to consider banning upstream dams or riverine disposal, another method of tailings management.

The Standard is not binding.

Part of the power imbalance was technical expertise. ICMM members employed top experts, and the PRI and UNEP were unable to keep pace, the authors say. Companies knew what kinds of facilities they wanted to build, and understanding what was important in building a dam helped tipped the balance in favor of those who built the dams.

However, Kemp says the Standard is not just the result of debates between communities and mining companies. Tailings dams require rigorous engineering. The final outcome was the result of debates over whether it should be a technical guidance focused on engineering, or whether it should include social and environmental considerations. Some stakeholders wrote that “Advocating zero tolerance [to human fatality] in respect of tailings failure may dilute the technical (standards) focus of the Standard…”

At the same time, the ICMM said they strived to create a standard that would have “zero tolerance for human fatality.” In at least two respects, the Standard fails, the authors write: dams that may kill up to 10 people may be built to lower standards; and the Standard implicitly assumes an “acceptable” level of risk. Who determines how much destruction is “acceptable”?

“I would want to challenge the claim that the ICMM made, that their interests were the most important in this game, because the most important interests are the project-affected people — in particular the people who live downstream from these facilities, whose lives are at stake,” Hopkins says.

Bruno Milanez, a professor at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora, joined the advisory panel midway through the process. He told me in a story for Mongabay last year that he almost didn’t join.

“These standards frequently have very little effectiveness,” Milanez said. “They create a lot of work for companies but produce limited concrete results.”

The original call came from investors, but they did not play much of a role. The expert panel could not work independently, and the UN Environment Program did not contribute its weight because it wanted the Standard to be independent, Kemp says. In the end, mining companies, represented by the ICMM, exercised an inordinate amount of power.

Kemp and Hopkins write that the investors, in bringing mining companies to the negotiating table, won round 1. Round 2 went to the CEOs represented by ICMM. Round 3, or implementation of the standard, is next. To this end, the UNEP announced in December a partnership to create an independent body that would monitor tailings management.

In Kemp’s 15 years of publishing, no other piece of research has received as much response as this book has. Mining executives have asked her to present to their companies. Others have called her colleagues to question why she felt the need to publish the book in the first place. “It wasn’t meant to be a secret process,” she says.

“There are going to be more tailings facilities in the future, not fewer, so the pedal should be going down hard. To me, it’s a mild acceleration at most — at least on the social performance aspects,” Kemp says.

Nice article. I just subscribed and going through the archive. I see some startups that are specifically going after using tailings as a resource. I suspect for vast majority of tailings, its not economical to further process it. Is that correct, any other barriers preventing further extraction ? What do you think are the best opportunities for these startups ?