What if seabed mining goes wrong?

Citizens of Tonga are demanding answers about liability

Climate technologies require enormous amounts of metal. I’m Ian Morse, and this is Green Rocks, a newsletter that doesn’t want dirty mining to ruin clean energy. Sign up to receive weekly updates:

[I developed this story with further investigation into a story with Mongabay.]

Pelenatita Kara regularly travels to the outer islands of Tonga, her low-lying Pacific Island home, to educate fishers and farmers about seabed mining. For many of the people she meets, seabed mining is an unfamiliar term. Before Kara began appearing on radio programs, few people knew their government had sponsored a company to mine metals from the deep ocean.

“It’s like talking to a Tongan about how cold snow is,” she told me recently. “Inconceivable.”

This distance from seabed mining — in addition to the physical 4,000 mile distance from the exploration area — concerns Kara, who works with the Civil Society Forum of Tonga. As a sponsor state, Tonga has agreed to shoulder a significant amount of responsibility for the company, a player in this fledgling industry that may threaten ecosystems that are barely understood, according to scientists.

“My concern is that the liability from any problem with deep-sea mining will just be too much for us,” Kara says.

Since the end of last year, Kara’s organization and other international groups have been writing to several governments, as well as the International Seabed Authority, which is tasked with regulating the high seas where mining is set to occur. The ISA is writing operating regulations, which would pave the way for mining to begin.

“The Pacific is currently the world’s laboratory for the experiment of Deep Seabed Mining,” Kara and the other groups wrote to the ISA. And if anything goes wrong in the lab, Kara is worried that her country wouldn’t be able to foot the bill. And if no one can pay for remediation, Greenpeace notes, that may be even worse.

The company sponsored by Tonga’s government is owned by DeepGreen, a Canadian company that claims the minerals it could scrape from the seabed are necessary to build enough electric vehicles to avert climate disaster. A DeepGreen-funded study has shown that seabed mining would dramatically reduce the carbon footprint of battery materials. (The study assumes no mining would take place on land if seabed mining goes ahead.)

Seabed mining has never been attempted here, or at such scale anywhere. In response to environmentalists’ concerns that ecosystems would be wiped out before they’re understood and can contribute to science, several prominent companies, like Google and BMW, said they would refuse metals sourced from the ocean until the risks are fully understood.

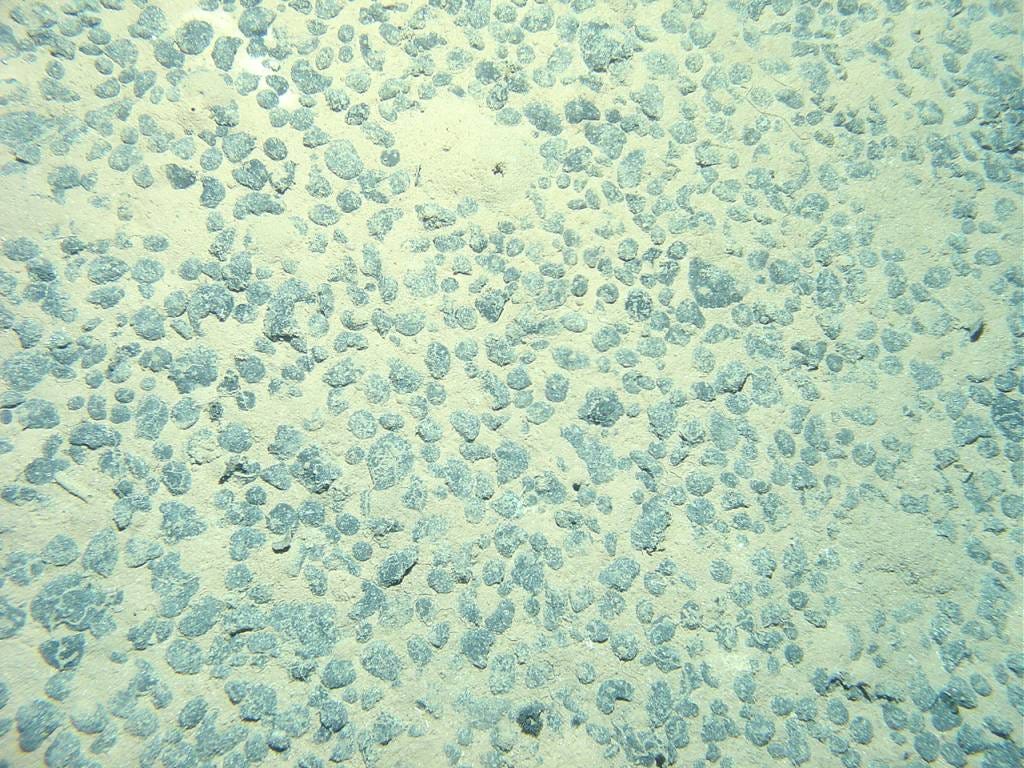

DeepGreen responded strongly, saying “Consumer brands that refuse to consider alternative mineral supplies will be complicit in increased deforestation, toxic tailings, child labour (in the case of cobalt), and destruction of terrestrial habitats and carbon sinks.” DeepGreen is also pumping $60 million into ocean research in the mining area (shown below).

The company

Tonga Offshore Mining Limited (TOML) is DeepGreen’s Tonga-supported business. It has licensed several tracts of ocean in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an area between Hawaii and Mexico. TOML began its life as a subsidiary of Nautilus minerals, one of the world’s first deep-sea miners. Just before Nautilus’ project in Papua New Guinea’s waters failed and left the country with $157 million in debt, shareholders created DeepGreen. Last year, DeepGreen, a Canadian company led by an Australian, bought TOML.

DeepGreen has said it is giving “developing” states like Tonga the opportunity to benefit from seabed mining without shouldering the commercial and technical risk. For Kara, that doesn’t include the environmental and financial risks.

“I am afraid that Tonga will be another Papua New Guinea,” Kara says. “If they start mining and something happens out there, we don’t have the resources, the expertise, because we need to validate what they’re doing,” she said.

In 2011, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea warned that companies in “developed states” who get sponsorship from developing states in the hopes of “less burdensome regulations and controls” may jeopardize ocean protection.

Can a country sponsor a company it can’t control?

The failure in PNG raises significant concerns about liability. Problems may occur in the CCZ: sediment plumes may travel thousands of kilometers and obstruct fisheries, or damages could stretch into other companies’ areas. Scientists don’t know all the possible consequences, in part because ecosystems are poorly understood.

If something does go wrong, people will look to regulations. The UN created the ISA to write these regulations on behalf of all humankind. Under current rules, Tonga may only be liable for damages if it fails to fulfill its obligations as a sponsor, which include conducting due diligence on TOML and doing whatever it can to ensure TOML is held to the highest standards of environmental safety. That means Tonga must have the ability to enforce its regulations and the ability to create strict regulations on an untested industry. This is a tall order.

Kara, however questions whether Tonga can adequately control TOML, its management, and its activities. TOML is registered in Tonga, but its management consists of DeepGreen Australian and Canadian employees. It is owned by a Canadian company. TOML is a Tongan company, but it seems only because it was once registered there.

Sponsoring states must have “effective control” over the companies they sponsor, but the ISA has not explicitly defined what that means. For example, TOML’s exploration contract says that if “control” changes, it must find a new sponsoring state. Last year, DeepGreen acquired TOML, and the only Tongan national in the company was no longer listed in management. Without a definition of “control,” people disagree whether Tonga can still sponsor TOML.

“Of all the work they’re doing in the area, I don’t know whether there’s any Tongan sitting there, doing the so-called validation and ascertaining what they do. We’re taking all of this at face value,” Kara says. With few resources to track down people who live in Canada or Australia, Kara is worried that Tonga will not be able to hold foreign individuals accountable for problems that may arise.

So, the question is: Who controls TOML?

On paper, TOML is Tongan. Financially, Canada controls its assets. In management, it’s Canadians and Australians.

Additionally, DeepGreen plans to go public at least partially through a US-based company. Part of TOML’s financial or economic control will be with shareholders of a US company on the New York stock exchange. The US, however, has not signed on to the UN convention that guides the ISA. The US, then, is not bound by ISA regulations, the only authority governing mining on the high seas.

When Kara’s Civil Society Forum of Tonga and others wrote to the ISA, they argued Canada should sponsor TOML, considering a fair amount of control was within Canadian borders. In response, the ISA wrote that the Tongan government “has no objection” to the management changes, so no change was needed. (The Tongan government retains the right to cancel sponsorship of TOML.)

“What I think is pretty clear is that ‘effective control’ means economic, not regulatory, control,”says Duncan Currie, a lawyer who advises conservation groups on ocean law. “So wherever it is, it's not in Tonga.”

Economic development from selling EVs

Tonga stands to earn royalties from seabed mining activities. According to the latest information, Tonga will receive $1.25 for every ton of nodules. That may be 0.16% of the value of the activities it sponsors, according to scenarios presented to the ISA by a group from MIT. Royalties paid to the ISA and then distributed to countries may be around $100,000.

“I’m still trying to figure out their angle. Personally, I think DeepGreen is using Pacific Islanders to hype their image. I’m still thinking that we were never really the target. The shareholders have always been their target,” Kara says.

Kara doubts the minerals at the bottom of the ocean are needed for drivers to stop burning fossil fuels. In a letter to a Tongan newspaper, Kara wrote:

Deep-sea mining is a relic, left over from the extractive economic approaches of the ’60s and ’70s. It has no place in this modern age of a sustainable blue economy.

As Pacific Islanders already know – and science is just starting to learn – the deep ocean is connected to shallower waters and the coral reefs and lagoons. What happens in the deep doesn't stay in the deep.

The ISA and DeepGreen did not respond to questions before publication.

Thank you! As someone who has been campaigning against the issue of deep sea mining for over a decade and more broadly the greenwashing of extractivism for over two decades it is heartening to see such brilliant journalism that centres the most important voices. Our partners in the Pacific need intelligent reporting like this. On behalf of the Deep Sea Mining Campaign we will make sure this is disseminated far and wide.

Nat Lowrey

Nat's right. But what I want to add is that in terms of the specific concerns expressed in the article, I would think that a security deposit would be a good start. It would be useful to know why and how the PNG ended up such a large debt following the Nautilus collapse (the debt was news to me). Alternatively, I wonder whether any insurance company would insure TOML against failure. Has this been done elsewhere? As for the Tongan fishermen, the concern would presumably be with the outfall (rather than the collector), which is supposed to occur below the level at which it can affect the upper few hundred metres. However, large "cold-core" eddies can draw water from similar depths. That would be my concern. It may be that Deep Green has already taken them into account in their planning, but I have not found specific mention of it.